Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone, Lord Chancellor at the time of Lord Denning's retirement, suggested that Lord Denning's arrival at the English Court of Appeal had coincided with the conclusion of a period of thirty-five years following which he said:

Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone, Lord Chancellor at the time of Lord Denning's retirement, suggested that Lord Denning's arrival at the English Court of Appeal had coincided with the conclusion of a period of thirty-five years following which he said:"Our Lady of the Common Law awoke from her slumbers and entered upon a period of renewed creativity, generated no doubt by the vast social and legislative changes which have overtaken us, and inspired by a desire to do right to all manner of people without fear or favour, affection or ill-will in the changed circumstances of the post-War world".

In so many areas of public and private law, Lord Denning brought fresh insights and impatience with blind adherence to old formulations of the law where these appeared out of harmony with a sense of the just result of the particular case.

When Lord Denning urged a new approach to statutory interpretation, he attracted the censure of the London Times editorialist, in those days immovably orthodox:

"What Lord Denning is trying to do is to import into the interpretation of statutory provisions the same degree of judicial creativity as is normally applied to developing the common law. The tradition of English law does not support that approach. It may be acceptable to introduce a qualified element of equity into the harsh rules of statutory construction. [But] this would be under his formula for the majority of judges to determine a sensible result. That would be to usurp Parliament's function and give judges a power which the vast majority of them neither seek nor are capable of exercising".

Denning's focus on function rather than form shaped his approach to judicial precedents, as it had his views on statutory and documentary construction. His beliefs emerge clearly from the following:

"If lawyers hold to their precedents too closely, forgetful of the fundamental principles of truth and justice which they should serve, they may find the whole edifice comes tumbling down about them. They will be lost in the 'codeless myriad of precedent. That wilderness of single instances'. The common law will cease to grow. Like a coral reef, it will become a structure of fossils." (Ref: From Precedent to Precedent, p. 3)

"It seems to me that when a particular precedent, even in Your Lordship's house, comes into conflict with a fundamental principle, also of Your Lordship's house, then the fundamental principle must prevail. This must at least be true when on the one hand, the particular precedent leads to absurdity or injustice, and on the other hand, the fundamental principle leads to consistency and fairness. It would, I think, be a great mistake to cling too closely to a particular precedent at the expense of fundamental principal". London Transport Executive v. Botts (1959) AC 213

"The Doctrine of Precedent does not compel Your Lordship to follow the wrong path until you fall over the edge of the cliff. As soon as you find that you are going in the wrong direction you must at least be permitted to strike off in the right direction, even if you are not allowed to retrace your steps". Ostine (Inspector of Taxes) v. Australian Mutual Provident Society (1960) AC 459

"Many a lawyer will dispute the analogy with science. 'I am only concerned', he will say, 'with the law as it is, not with what it ought to be'. For him the rule is the thing. Right or wrong does not matter. That approach is all very well for a working lawyer who applies the law as a working mason lays bricks, without any responsibility for the building which he is making. But it is not good enough for the lawyer who is concerned with his responsibility to the community at large. He should ever seek to do his part to see that the principles of law are consonant with justice. If he should fail to do this, he will forfeit the confidence of the people. The law will fall into disrepute; and if that happens, the stability of the country will be shaken. The law must be certain. Yes, as certain as may be. But it must be just too". (Ref: From Precedent to Precedent, p. 4.)

"Even more so when we come to the meaning of words. Lawyers are here the most offending souls alive. They will so often stick to the letter and miss the substance. The reason is plain enough. Most of them spend their working lives drafting some kind of document or another - trying to see whether it covers this contingency or that. They dwell on words until they become mere precisions in the use of them. They would rather be accurate than clear. They would sooner be long than short. They seek to avoid two meanings, and end - on occasion - by having no meaning". Ibid, p. 15

"Let it not be thought from this discourse that I am against the Doctrine of Precedent. I am not. It is the foundation of our system of case law. This has evolved by broadening down from precedent to precedent. By standing by previous decisions, we have kept the common law on good course. All that I am against is its too strict application, a rigidity which insists that a bad precedent must necessarily be followed. I would treat it as you would a path through the woods. You must follow it certainly, so as to reach your end, but you must not let the path become too overgrown. You must cut out the dead wood and trim off the side branches, else you will find yourself lost in the thickets and the brambles. My plea is simply to keep the path to justice clear of obstructions which impede it". (Ref: The Discipline of Law, p. 314.)

Of Denning's common law cases, Professor Atiyah wrote:

"...What is most striking about his contribution to the common law is the number of times in which his views, while originally being received with doubt or rejection, have ultimately been vindicated".

"...What is most striking about his contribution to the common law is the number of times in which his views, while originally being received with doubt or rejection, have ultimately been vindicated".

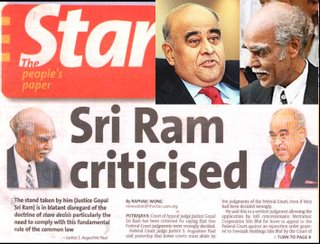

It is interesting today to compare the restrained comment and the similarity of language that Federal Court judge Augustine Paul uses today.

Influence is one thing. Denning wielded it with the assurance of a "supremely able person".

For Denning, creativity was part of the genius of the common law. Where else did the principles of the common law come from except the creative minds of the judges of the past searching the casebooks for just solutions to new problems? Why, he constantly asked himself, was there a demand that, in this age, the element of creativity and development of legal principle should be dropped? The suggestion that this was so out of deference to an elected Parliament scarcely carried conviction for him. All too often, Parliament ignored the multifarious needs of law reform: its eyes fixed on the large political debates and the battles for office. Yet the pressures of change and the needs for reform were greater at this time than ever because of changing social, technological and governmental developments.

The Hon Justice Michael Kirby has this to add:

We need a modern Denning with great experience and skills of communication, to rise above the chorus of publicised opprobrium. And to explain that the element of creativity, properly harnessed and well directed, is not a weakness of the common law system. It is a mighty strength. It helps to explain the survival of the common law as one of the greatest of the legacies of the British Empire. It helps to avoid stamping, unquestioned, on one generation, the morality, attitudes and social rules of the distant past. Lord Denning, as a leading judge, would have spoken up himself, as he always did with good humour to answer selected critics. As a court leader he would have encouraged a more effective response from the courts to communicate their decisions to the public and to explain their techniques and the necessities of occasional judicial creativity. He would have urged the Bar and other members of the legal profession to take a lead in responding to unmerited attacks on the judiciary who, as he once pointed out, are generally not well placed to answer back. He would have called for mutual respect between the branches of government as each branch performs the functions proper to itself. He would have encouraged a return to the education of the citizenry in civics so that they would understand their national constitution and the vital role of the judges in its scheme.

The judges of today who follow as lineal descendants in the common law judiciary, can take strength from the fortitude of Lord Denning, his good humour in the face of criticism and Lordly rebukes, his faithful adherence to principles of free speech and his unapologetic dedication to refurbishing the common law, as his great predecessors had done before him. When, like Lord Denning, one has a perspective of a century, the gales of abuse are seen for what they are. Passing things. The storms come and go. The judicial institution goes on. The judges continue to make their decisions with obedience to statutory law as they construe it and faithful reliance upon legal authority as they define it but with the stimulation of legal principle and legal policy where that is needed to avoid plain injustice and to reverse a wrong turning.

We, his successors throughout the world, are not mechanics of the law. We are a profession sworn to justice. That is what gives the law its claim to moral nobility. This remains Denning's great instruction to us. Even when the din of attack, the superficial political labels and the pressure of criticism become most vocal (perhaps especially then) the independent judges of the common law must remain steadfast and self-confident in their vocation. The times have changed significantly since Denning served as a judge. It is given to few to serve as long or as brilliantly. But every judicial officer of the common law, high and low, is reminded by Denning's life and work that creativity is part of the genius of our vocation. We must explain this to each succeeding generation of lawyers, as Denning, by his example and ceaseless efforts, tried to do. We must seek to explain it to citizens beyond the courtroom so that, like Denning, they honour and cherish the common law. We must remember it for ourselves.

This is Lord Dennings advice to judges:

"A judge must not alter the material of which it is woven, but he can and should iron out the creases".

In conclusion let's read the Practice Statement by Lord Chancellor, Lord Gardiner:

"Their Lordships regard the use of precedent as an indispensable foundation upon which to decide what is the law and its application to individual cases. It provides at least some degree of certainty upon which individuals can rely in the conduct of their affairs, as well as a basis for orderly development of legal rules.

Their Lordships nevertheless recognise that too rigid adherence to precedent may lead to injustice in a particular case and also unduly restrict the proper development of the law. They propose, therefore, to modify their present practice and, while treating former decisions of this House as normally binding, to depart from a previous decision when it appears right to do so.

In this connection, they will bear in mind the danger of disturbing retrospectively the basis on which contracts, settlements of property, and fiscal arrangements have been entered into and also the especial need for certainty as to the criminal law.

This announcement is not intended to affect the use of precedent elsewhere than in this House."

Epilogue

The law will stand still while the rest of the world goes on; and that would be bad for both".

1 comment:

How I Got My Loan From A Genuine And Reliable Loan Company

I am Mrs.Irene Query i was in need of a loan of S$70,000 and was scammed by those fraudulent lenders and a friend introduce me to Dr Purva Pius,and he lend me the loan without any stress,you can contact him at urgentloan22@gmail.com

1. Your Full names:_______

2. Contact address:_______

3. Country Of Residence:______

4. Loan Amount Required:________

5. Duration:_____

6. Gender:_____

7. Occupation:________

8. Monthly Income:_______

9. Date Of Birth:________

10.Telephone Number:__________

Regards.

Managements

Email Us: urgentloan22@gmail.com

Post a Comment