This landmark case arose out of the 1993 tragedy of the collapse of a tower block in the Highland Towers development in Ampang, just outside the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur leading to loss of life and the loss of use of the Blocks that remained standing.

This landmark case arose out of the 1993 tragedy of the collapse of a tower block in the Highland Towers development in Ampang, just outside the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur leading to loss of life and the loss of use of the Blocks that remained standing.The event gained widespread publicity at the time, in particular as it was captured by a dramatic sequence of photographs taken by an American visitor to the Towers, and the frantic rescue operations over the next ten days.

The case has several important implications for local authorities and Building Professionals in Malaysia, and also led to interesting developments and clarifications in the law of tort in Malaysia.

Brief facts

Highland Towers consisted of three blocks 12 storey high apartments named simply as Block 1, 2 and 3 respectively. It was constructed sometime between 1975 and 1978. Directly behind the 3 blocks was a steep hill with a stream flowing west (“the East Stream”), which would have passed harmlessly to the south of the Highland Towers site if it was allowed to follow its natural course.

Some time in the course of the Highland Towers development (as found by the Court) the East Stream was diverted by means of a pipe culvert to flow northwards across the hillslope directly behind Highland Towers. The approved drainage system on the hillslope behind Highland Towers was never completed.

On Saturday, the 11th December 1993, at about 1.30p.m., after 10 days of continuous rainfall, Block 1 collapsed.

Cause

The landslide that brought down Block 1 of Highland Towers was found by the Court to have been a rotational retrogressive slide emanating from a high retaining wall behind the 2nd of a 3-tier car park serving the 3 blocks of the Highland Towers.

Water was found to be one of the factors that caused this high wall to fail. This water emanated from poor and nonmaintained drainage, as well as a leaking pipe culvert carrying the waters of the diverted East Stream.

Liability

The following were the findings on liability by the Court:

The First Defendant (Developer) was liable in negligence for not engaging a qualified architect, constructing insufficient and inadequate terraces, retaining walls and drains on the hillslope which could reasonably have been foreseen to have caused the collapse diverting the East Stream from its natural course and failing to ensure the pipe culvert diversion was adequate, and in nuisance for not maintaining drains and retaining walls.

The Second Defendant (Architect) was liable in negligence for not having ensured adequate drainage and retaining walls were built on the hillslope adjacent to the Highland Towers site, which he foresaw or ought to have foreseen would pose a danger to the buildings he was in charge of, in not complying with the requirements of the authorities in respect of drainage, in colluding with the First Defendant and Third Defendant (the Engineer) to obtain a Certificate of Fitness without fulfilling the conditions imposed by the Fourth Defendant (the Local Authority), in so doing not complying with his duties as Architect, and in not investigating the terracing of the hillslopes and construction of retaining walls even though he was aware they would affect the buildings he was in charge of, and also in nuisance as he was an unreasonable user of land.

The Third Defendant (Engineer) was liable in negligence for not having taken into account the hill or slope behind the Towers, not having designed and constructed a foundation to accommodate the lateral loads of a landslide or alternatively to have ensured that the adjacent hillslope was stable, for not having implemented that approved drainage scheme, for colluding with the First and Second Defendants to obtain a Certificate of Fitness without fulfilling the conditions imposed by the Fourth Defendant and also in nuisance as he was an unreasonable user of land.

The Fourth Defendant (Local Authority) although negligent in respect of its duties associated with building. i.e. in respect of approval of building plans, to ensure implementation of the approved drainage system during construction, and in the issue of the Certificate of Fitness, was nonetheless conferred immunity by reason of s95(2) of the Street, Drainage and Building Act.

The Fourth Defendant was however not immune in respect of its negligence in carrying out its post building functions of maintaining the East Stream. This also attracted liability in nuisance.

The Fifth Defendant (Arab-Malaysian Finance Bhd) was liable in negligence in failing to maintain the drains on its land, and in taking measures to restore stability on its land after the collapse.

The Sixth Defendant (an abortive purchaser of the Arab-Malaysian Land who carried out site clearing works) was not found liable on the evidence.

The Seventh Defendant (Metrolux Properties) and the Eighth Defendant (Metrolux Project Manager), who were liable in negligence and nuisance for preventing water from flowing downhill (into their site) and instead directing water into the East Stream, when they knew or ought to have known that this would increase the volume of water and inject silt, especially where there was extensive clearing on their land, into the East Stream where it would be deposited, which would in turn (as proved) cause or contribute to the failure of the drainage system and collapse of Block 1.

The Ninth and Tenth Defendants (essentially the State Government) were held not iable due to a technical issue in respect of the particular party sued.

Rule In Rylands v Fletcher

In this cause of action, if a person brings unto his land and collects and keeps anything to do with mischief and it escapes, he is answerable prima facie for all the damage which is the natural consequence of the damage, regardless of whether the Defendant was negligent or not. The Highland Towers decision, following the Australian High Court in Burnie Port Authority v General Jones Pty Ltd 120 ALR 42 abandoned this as an independent cause of action and merged it into the general law of negligence.

From the principles laid down in the Court of Appeal judgment, the Highland Towers decision clarifies the extent and nature of the professional duties and responsibilities of Building Professionals demanded by the law, and contains important developments in tort law in Malaysia.

Howeve this decision of the Court of Appeal remains subjected to the Highest Court, i.e. the Federal Court, whether they would endorse these principles.

Final Judicial Decision

Today, 18th February 2006 frontpage headline the Federal Court's DecisionFederal Court: MPAJ has full immunity from claims

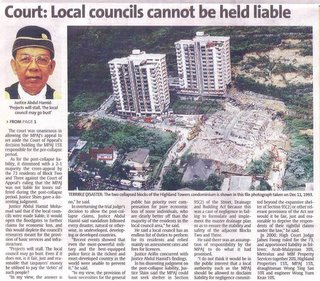

Local councils cannot be held liable for losses suffered by anyone should a building collapse, the Federal Court has ruled. The court said this when it held that the Ampang Jaya Municipal Council (MPAJ) was not liable for losses suffered by 73 residents of two blocks of the Highland Towers condominium who had to evacuate after the collapse of Block One 13 years ago, killing 48 people.

The three-member panel presided by Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak Justice Steve Shim Lip Kiong and Federal Court judges Datuk Abdul Hamid Mohamed and Datuk Arifin Zakaria ruled that the MPAJ was not liable in the pre-collapse period as well as post-collapse period of Block One. They said local authorities such as the MPAJ were given full immunity under Section 95 (2) of the Street, Drainage & Building Act 1974 (Act 133) from claims for the pre-collapse period.

The court was unanimous in allowing the MPAJ’s appeal to set aside the Court of Appeal’s decision holding the MPAJ 15% responsible for the pre-collapse period. As for the post-collapse liability, it dismissed with a 2-1 majority the cross-appeal by the 73 residents of Block Two and Three against the Court of Appeal’s ruling that the MPAJ was not liable for losses suffered during the post-collapse period.

Justice Shim gave a dissenting judgment.

Justice Abdul Hamid Mohamad said that if the local councils were made liable, it would open the floodgates to further claims for economic loss, and this would deplete the council’s resources meant for the provision of basic services and infrastructure. “Projects will stall. The local council may go bust. Even if it does not, is it fair, just and reasonable that taxpayers’ money be utilised to pay the ‘debts’ of such people? In my view, the answer is no,” he said.

In overturning the trial judge’s decision to allow the post-collapse claims, Justice Abdul Hamid said vandalism followed every disaster, natural or otherwise, in undeveloped, developing or developed countries. “Recent events showed that even the most-powerful military and the best-equipped police force in the richest and most-developed country in the world were unable to prevent it,” he said.

“In my view, the provision of basic necessities for the general public has priority over compensation for pure economic loss of some individuals, who are clearly better off than the majority of the residents in the local council area,” he said.

He said a local council has an endless list of duties to perform for its residents and relied mainly on assessment rates and fees for licences.

Justice Arifin concurred with Justice Abdul Hamid’s findings.

In his dissenting judgment on the post-collapse liability, Justice Shim said:

"The MPAJ could not seek shelter in Section 95(2) of the Street, Drainage and Building Act because this was a case of negligence in failing to formulate and implement the master drainage plan so as to ensure the stability and safety of the adjacent Blocks Two and Three."

He said there was an assumption of responsibility by the MPAJ to do what it had promised.

“I do not think it would be in the public interest that a local authority such as the MPAJ should be allowed to disclaim liability for negligence committed beyond the expansive shelter of Section 95(2) or other relevant provisions of the Act nor would it be fair, just and reasonable to deprive the respondents of their rightful claims under the law,” he said.

In 2000, High Court Judge James Foong ruled for the 73, and apportioned liability as follows: Arab-Malaysian 30%, Metrolux and MBf Property Services together 20%, Highland Properties 15%, MPAJ 15%, draughtsman Wong Ting San 10% and engineer Wong Yuen Kean 10%.

Conclusion

The case is put to rest. The local authorities received the legal mandate that they are fully immune to liabilities. Even in committing reckless negligence, they will be shielded by the law under Section 95(2). Presumably, they could be care-free in all their ways of doing things and approving anything they deem fit in their full discretion, without the need to consider any threats to life, or to others.

It is the sad day for the Rule of Law in Malaysia.

Only if, and only if, we still can take the case to the UK Privy Council, can be hope to seek natural justice and the fundamental Rule of Law.

I Cry for You, Malaysia!!!

Note: Read the case study here

6 comments:

This is really so very sad, isn't it?

I watched the tragedy and rescue effort on TV so many years ago and the memory of it stays on to this day. I remember shedding tears for the mother who lost her newborn baby, for another mother who, while in the hospital recuperating from giving birth to a baby girl but lost all three sons in the collapsed apartment and also Dr Benjamin George who lost his wife and children. And so many others ...

It must have been heart-wrenching for those who have fought this case all these years to see it come to this ending.

Thanks for the write-up.

2 words: Mati katak. When r u becoming a full lawyer btw? I find your service got diskaun har?

I was there when this happened. It was sad, This tragedy changed my whole life. I'm glad that I risked my life to go into this building and recovery those who lost their lives. I was working the D area in fact in the picture above it would be the lower right hand side where the cranes were. I did this because my heart was for everyone of those people. What I saw there I will never forget. I visited Malaysia recently and saw that someone had stole the plaqe that once stood there. how can people do this? even for the fact that during the rescue people were stealing valueable items. thats a disgrace. I remember Dr. George. I wept for his loss. I still shed a tear when I think about it today.

Larry

Larry,

Thank you for sharing with us your empathy.

I would be please if you could contribute an article based on your life experience at Highland Tower.

I am not sure whether you will be back here to read this.

i don't understand some of this article,who was liable to this case?can someone explain to me?

Arab Malaysian paid some RM52 million to the owners of block 2 and 3 who filed the suit on 10 parties.

As for the owners (or their next of kin) of the 1st block, who compensated for their losses.?

Post a Comment